Introduction

Late in summer 2017, Bosch, one of the leaders in automotive components, threw a challenge to Udacity learners.

The aim of the challenge was to have a (simulated) car drive itself autonomously along a three-lane, 7-km highway loop, in traffic, without colliding with other vehicles on the road. The autonomous vehicle (called the ego car) should observe all the rules of the road:

- Drive at max speed 50 miles/hour

- Pass slow moving vehicles on the road

- Automatically accelerate/slow down, brake, as needed to avoid collisions

- Observe lane change rules - e.g. change lanes smoothly

- Should not cross into incoming traffic

- Max acceleration: 10 m/s^2 - to maintain passenger comfort

- Max jerk: 10 m/s^3 (rate of change of acceleration) - to maintain passenger comfort

- Complete the track around the loop, and drive at least ~5 miles without any violations(incidents)

In order to achieve a safe and smooth autonomous driving experience, the ego car must use sensor fusion data, localization, map information to accurately predict its future trajectory, and execute it correctly.

Summary

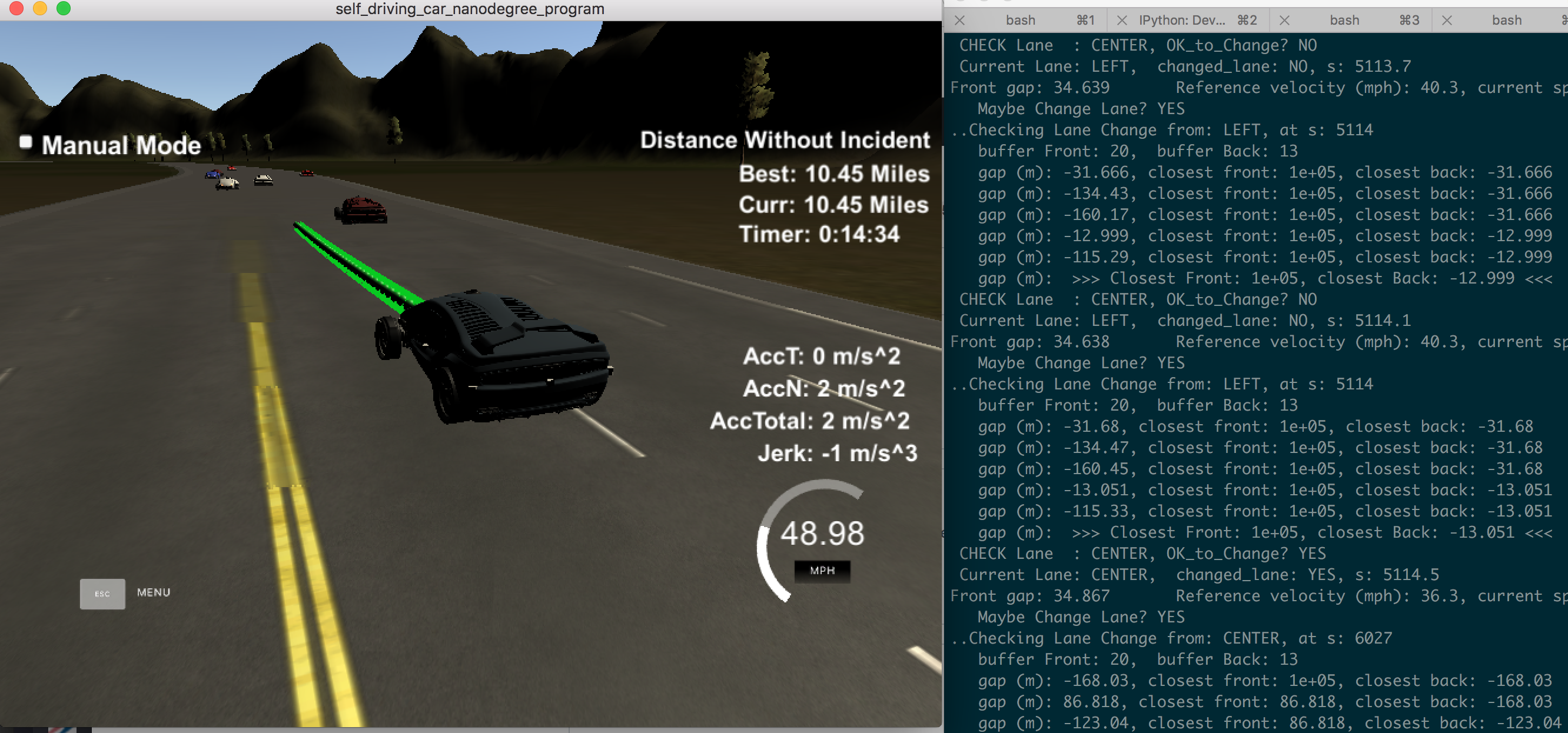

My self-driving car successfully completed the Bosch Path Planning challenge, and was one of the top 25 entries, from among hundreds of entries. 👍🚗🍾 Niiice

Check out the video below (click on the image). Best way is to watch it at 2x speed.

Here’s the Youtube video.

What is Path Planning

Path planning, also called motion planning is one of the most challenging problems in autonomous driving. It typically consists of three functions: Prediction, Behavior Planning, and Trajectory Generation.

- Prediction The predictor asks the question: Who is moving around me, and where? This function concerns with predicting the behavior of other moving objects around our (ego) autonomous vehicle, such as other cars, bicycles, pedestrians, etc. How is this achieved? In a nut shell, there are two main approaches: process model approach and data-based approach.

The process model approach typically uses probabilistic methods to guess where and when each moving object will move next. Recall that sensor fusion data periodically gives our ego vehicle information about where each moving object is. Thus, the ego car predicts (with a certain probability) where other vehicles will be next, and updates its (incorrect) guesses based on (updated) actual sensor data.

The data based approach uses machine learning techniques to predict how likely some vehicle will turn right/left/go straight at an intersection, for example. This approach obviously uses a lot of training data.

Regardless of the approach used, the planner makes an (accurate enough) estimate of next positions of other, relevant vehicles.

Behavior planning The behavior planner answers the question: What should I do next? Given that other vehicles, pedestrians, etc. might be moving, how should our ego vehicle move? The behavior planner determines which maneuvers to execute, taking into account its own destination, and the predicted behavior of other dynamic objects around it. For example, the behavior planner could plan to slow down (if a car infront is slowing down), brake (if a pedestrian suddenly comes in its way), change lanes (if it becomes available, or to avoid a slow vehicle), and so on.

Trajectory generation The trajectory generator answers the question: What precise path should I follow next? It takes the ego vehicle’s planned behavior and plots a precise trajectory to take. This requires generating dozens (or more) trajectories per second, evaluating costs for each, and choosing a trajectory that satisfies the “best” conditions.

The trajectory generator takes into account important safety and comfort variables, such as speed limit (different for highway and urban driving), maximum forward and sideways acceleration and jerk (for comfort), its own body weight, etc. The best trajectory is one that has the lowest cost (where a cost is a penalty for violating safe and comfortable driving conditions).

Approach

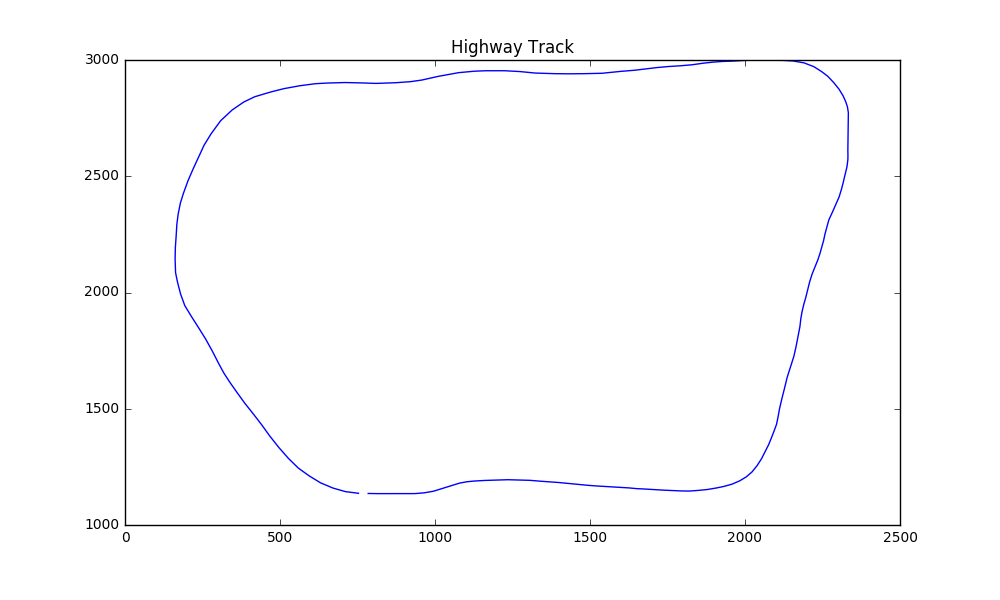

Highway Track

Highway Track

Coordinates

We use Frenet coordinates (s, d) instead of regular X,Y coordinates as this simplifies the path planning. In Frenet coordinates, s denotes longitudinal displacement along the road, while d denotes lateral displacement from the center (yellow) dividing line. The track is approx. 6947 meters long, thus s varies from 0-6947 (length of the track). The d value shows distance away from center divider: each lane is 4 meters wide, and there are three lanes: Left, Center, Right. Thus, the d value for Left lane will be 0 < d < 4, for Center lane (4 < d < 8), and for Right lane (8 < d < 12). Thus, the (s,d) coordinates fully specify a car’s position on the track.

We use Frenet coordinates with transforms and spline interpolation to generate paths. As the picture above shows, the highway map is a loop, and in Frenet coordinates the outline is jagged and has sharply cut line segments. This results in sharp acceleration and jerk around the corners. To help smooth this out, spline interpolation was used.

The key elements of the project are broken down into three parts:

- Sensor Fusion: understanding (nearby) traffic

- Path Planning: determining lane change behavior

- Trajectory construction

Sensor Fusion - Analyzing Traffic Information

In a typical self-driving car, various sensors (LIDARs, radars, cameras, etc.) continously provide enviroment information to answer key questions: What objects are nearby? How far are they? Are they static or dynamic? How fast and in what direction are they traveling? Etc.

The simulator in this particular case provides a smaller subset of information: Cars traveling in this side of the ego car. It does not provide any info on cars in the opposite side of the road (i.e. on-coming traffic). The highway track is a 3-lane highway on each side. The ego car starts in the Center lane, and then drives itself based on near-by traffic.

In my implementation, the ego car first analyzes sensor fusion data to determine its reference velocity:

– Is there a car in our lane, infront of us, within 30 meters? If so, follow its speed – Is there a car in our lane, within 20 meters? If so, slow down to something less than leading car’s speed – If no car ahead of us, maintain a reference speed of 49 miles/hour, so that we don’t violate speed limit

This is implemented in lines 275-332 of main.cpp.

// 2. ---- SENSOR FUSION PROCESSING ----

// Determine Reference Velocity based on nearby traffic

double CLOSEST_DISTANCE_S = 100000;

bool change_lane = false;

bool too_close = false;

for (int i = 0; i < sensor_fusion.size(); i++)

{

double other_d = sensor_fusion[i][6]; // other car's d

double other_lane = getCarLane(other_d); // other car's lane#

double other_vx = sensor_fusion[i][3];

double other_vy = sensor_fusion[i][4];

double other_car_s = sensor_fusion[i][5];

// if Other Car in Ego car's lane..

if (other_lane == LANE)

{

double other_speed = sqrt(other_vx * other_vx + other_vy*other_vy);

// project where Other Car will be in the next few steps

other_car_s += (path_size * TIME_INTERVAL * other_speed);

// find front gap

double front_gap = other_car_s - car_s;

// check if Other Car is ahead and by how much

if (front_gap > 0 && front_gap < FRONT_BUFFER && front_gap < CLOSEST_DISTANCE_S)

{

CLOSEST_DISTANCE_S = front_gap;

if (front_gap > FRONT_TOO_CLOSE) {

// follow the front car

REF_V = other_speed * MS_TO_MPH;

// Yes - try a lane change

change_lane = true;

cout << "Front gap: " << front_gap

<< "\tReference velocity (mph): "

<< setprecision(4)

<< REF_V

<< ", current speed: "

<< car_speed

<< endl;

} else { // FRONT TOO CLOSE!

// go slower than front car

REF_V = other_speed * MS_TO_MPH - 5.0;

too_close = true;

// Definitely do a lane change!

change_lane = true;

cout << "FRONT TOO CLOSE! " << front_gap

<< "\tReference velocity (mph): "

<< setprecision(4)

<< REF_V

<< ", current speed: "

<< car_speed

<< endl;

}

cout << " Maybe Change Lane? " << yes_no(change_lane) << endl;

}

} // if in my lane

} // sensor-fusion

Path Planning: Lane Change Behavior

For lane change behavior, we use some simple heuristics. The car prefers to stay in its lane, unless there’s traffic ahead, in which case, it will try to find a lane it can safely move into.

- Stay in the lane, and drive at reference velocity for as long as possible.

- If there’s traffic ahead (as determined above), flag for a lane change.

- First, check the traffic in the lane left of current lane (if it exists, i.e. if the ego car is not already in Left lane). Find the closest front and closest back gaps in this lane. Only if there’s enough space in the front (20 meter buffer) and back (13 meter buffer), set target lane to this lane.

- If the above (left-er) lane isn’t available to change into, check traffic in the lane right of the current lane (if such a lane exists, i.e. car is not already in the extreme Right lane). Perform the same evaluation, and set target lane to this lane.

// 3. --- LANE CHANGE LOGIC: Determine Target Lane (if needed) ---

int delta_wp = next_waypoint - lane_change_waypoint;

int remain_wp = delta_wp % waypoints.map_x_.size();

// cout << " delta wp : " << delta_wp << endl;

// cout << " map wp size: " << map_waypoints_x.size() << endl;

// cout << " remain wp: " << remain_wp << endl;

if (change_lane && remain_wp > 2)

{

cout << "..Checking Lane Change from: "

<< getLaneInfo(LANE)

<< ", at s: " << car_s << endl;

bool did_change_lane = false;

// First - check LEFT lane

if (LANE != LANE_LEFT && !did_change_lane) {

bool lane_safe = true;

// Check if OK to go LEFT?

lane_safe = is_lane_safe(path_size,

car_s,

REF_V,

LANE - 1, // To the Left of Current

sensor_fusion );

if (lane_safe) { // OK to go LEFT

did_change_lane = true;

LANE -= 1; // go Left by one lane

lane_change_waypoint = next_waypoint;

}

}

// NEXT - Try Right Lane?

if (LANE != LANE_RIGHT && !did_change_lane) {

bool lane_safe = true;

// Check if OK to go RIGHT

lane_safe = is_lane_safe(path_size,

car_s,

REF_V,

LANE + 1, // to the Right of Current

sensor_fusion);

if (lane_safe) { // OK to go RIGHT

did_change_lane = true;

LANE += 1; // go Right by one

lane_change_waypoint = next_waypoint;

}

}

cout << " Current Lane: "

<< getLaneInfo(LANE)

<< ", changed_lane: "

<< yes_no(did_change_lane)

<< ", s: " << car_s

<< endl;

} // if change lane

// --- END LANE CHANGE ---

is_lane_safe() implemented here:

// Path Planner -- Return TRUE if safe to change into given lane

bool is_lane_safe(const int num_points, // num of points to project speed for

const double ego_car_s, // Ego Car's s

const double ref_vel, // Ego Car's reference velocity

const double check_lane, // Lane to look for

const vector<vector<double> >& sensor_fusion_data)

{

bool ok_to_change = false; // should we move into the check_lane?

double SHORTEST_FRONT = 100000; // Really big

double SHORTEST_BACK = -100000;

cout << " Front buffer (m): " << LANE_CHANGE_BUFFER_FRONT

<< ", Back buffer: " << LANE_CHANGE_BUFFER_BACK << endl;

// Calculate the closest Front and Back gaps

for (int i = 0; i < sensor_fusion_data.size(); i++)

{

float d = sensor_fusion_data[i][6]; // d for a Traffic Car

double other_car_lane = getCarLane(d); // lane of the Traffic Car

// if a Traffic Car is in the lane to check

if (other_car_lane == check_lane) {

// get it's speed

double vx = sensor_fusion_data[i][3];

double vy = sensor_fusion_data[i][4];

double check_speed = sqrt(vx*vx + vy*vy);

// get it's s displacement

double check_car_s = sensor_fusion_data[i][5];

// see how far Other Car will go in TIME_INTERVAL seconds

// i.e. project its future s

check_car_s += ((double)num_points * TIME_INTERVAL * check_speed);

// see the gap from our Ego Car

double dist_s = check_car_s - ego_car_s; // WAS: ego_car_s

// remove -ve sign

double dist_pos = sqrt(dist_s * dist_s);

// store the shortest gap

// SHORTEST_S = min(dist_pos, SHORTEST_S);

if (dist_s > 0) { // FRONT gap

SHORTEST_FRONT = min(dist_s, SHORTEST_FRONT);

} else if (dist_s <= 0) { // BACK gap

SHORTEST_BACK = max(dist_s, SHORTEST_BACK);

}

cout << " gap (m): "

<< setprecision(5)

<< dist_s

<< ", closest front: "

<< setprecision(5)

<< SHORTEST_FRONT

<< ", closest back: "

<< setprecision(5)

<< SHORTEST_BACK

<< endl;

}

} // for-each-Traffic-car

cout << " gap (m): "

<< " >>> Closest Front: "

<< setprecision(5)

<< SHORTEST_FRONT

<< ", closest Back: "

<< setprecision(5)

<< SHORTEST_BACK

<< " <<< "

<< endl;

// Only if enough space in that lane, move to that lane

if ( (SHORTEST_FRONT > LANE_CHANGE_BUFFER_FRONT) &&

(-1 * SHORTEST_BACK > LANE_CHANGE_BUFFER_BACK))

{

ok_to_change = true;

}

cout << " CHECK Lane : " << getLaneInfo(check_lane) << ", OK_to_Change? " << yes_no(ok_to_change) << endl;

return ok_to_change;

} // end is-lane-safe

Trajectory Construction

As mentioned, we use Frenet coordinates (s, d) for path construction based on reference velocity and target d value for the target lane. Instead of a large number of waypoints, we use three waypoints widely spaced (at 30 meters interval) and interpolate a smooth path between these using spline interpolation. These are the anchor points. (This technique is discussed in the project walkthrough). To ensure that acceleration stays under 10 m/s^2, a constant acceleration is added to or subtracted from the reference velocity. The three anchor points are converted to the local coordinate space (via shift and rotation), and interpolated points are evenly spaced out such that each point is traversed in 0.02 seconds (the time interval). The points are then converted back to frenet coordinates, and fed to the simulator.

// 4.c In Frenet coordinates, add 30-meters evenly spaced points ahead of starting reference

double TARGET_D = 2 + LANE * 4; // d coord for target lane

vector<double> next_wp0 = getXY((car_s + SPACING), TARGET_D, waypoints.map_s_, waypoints.map_x_, waypoints.map_y_);

vector<double> next_wp1 = getXY((car_s + SPACING*2), TARGET_D, waypoints.map_s_, waypoints.map_x_, waypoints.map_y_);

vector<double> next_wp2 = getXY((car_s + SPACING*3), TARGET_D, waypoints.map_s_, waypoints.map_x_, waypoints.map_y_);

// Add these next waypoints to Anchor Points

anchor_pts_x.push_back(next_wp0[0]);

anchor_pts_x.push_back(next_wp1[0]);

anchor_pts_x.push_back(next_wp2[0]);

anchor_pts_y.push_back(next_wp0[1]);

anchor_pts_y.push_back(next_wp1[1]);

anchor_pts_y.push_back(next_wp2[1]);

// 4.d. Transform to Local coordinates

for (int i = 0; i < anchor_pts_x.size(); i++)

{

// SHIFT car reference angle to 0 degree

double shift_x = anchor_pts_x[i] - ref_x;

double shift_y = anchor_pts_y[i] - ref_y;

// ROTATION

anchor_pts_x[i] = (shift_x * cos(0 - ref_yaw) - shift_y * sin(0 - ref_yaw));

anchor_pts_y[i] = (shift_x * sin(0 - ref_yaw) + shift_y * cos(0 - ref_yaw));

}

// 4.e. Create a Spline

tk::spline s_spline;

// set Anchor points on the Spline

s_spline.set_points(anchor_pts_x, anchor_pts_y);

// 4.f. ADD points from Previous Path - for continuity

for(int i = 0; i < path_size; i++)

{

next_x_vals.push_back(previous_path_x[i]);

next_y_vals.push_back(previous_path_y[i]);

}

// 4.g. Target X and Y - Calculate how to break up spline points to travel at REF_VELOCITY

double target_x = SPACING; // HORIZON: going out to SPACING meters ahead

double target_y = s_spline(target_x);

double target_distance = sqrt((target_x * target_x) + (target_y * target_y));

double x_add_on = 0;

// 5. Fill up the rest of the path

for(int i = 1; i < 50-path_size; i++)

{

// if too slow, speed up by a small amount

if (car_speed < REF_V) {

car_speed += (MS_TO_MPH / 10); // 0.224;

} // else speed down by a small amount

else if (car_speed > REF_V) {

car_speed -= (MS_TO_MPH / 10); // 0.224;

}

// Calculate spacing of number of points based on desired Car Speed

double N = (target_distance / (TIME_INTERVAL * car_speed/MS_TO_MPH)); // num of points

double x_point = x_add_on + (target_x) / N;

double y_point = s_spline(x_point); // y on the spline

x_add_on = x_point;

double x_ref = x_point;

double y_ref = y_point;

// Transform coordinates back to normal

x_point = (x_ref * cos(ref_yaw) - y_ref * sin(ref_yaw));

y_point = (x_ref * sin(ref_yaw) + y_ref * cos(ref_yaw));

// Add to our Reference x, y

x_point += ref_x;

y_point += ref_y;

// FINALLY -- add to our Next Path vectors

next_x_vals.push_back(x_point);

next_y_vals.push_back(y_point);

Results

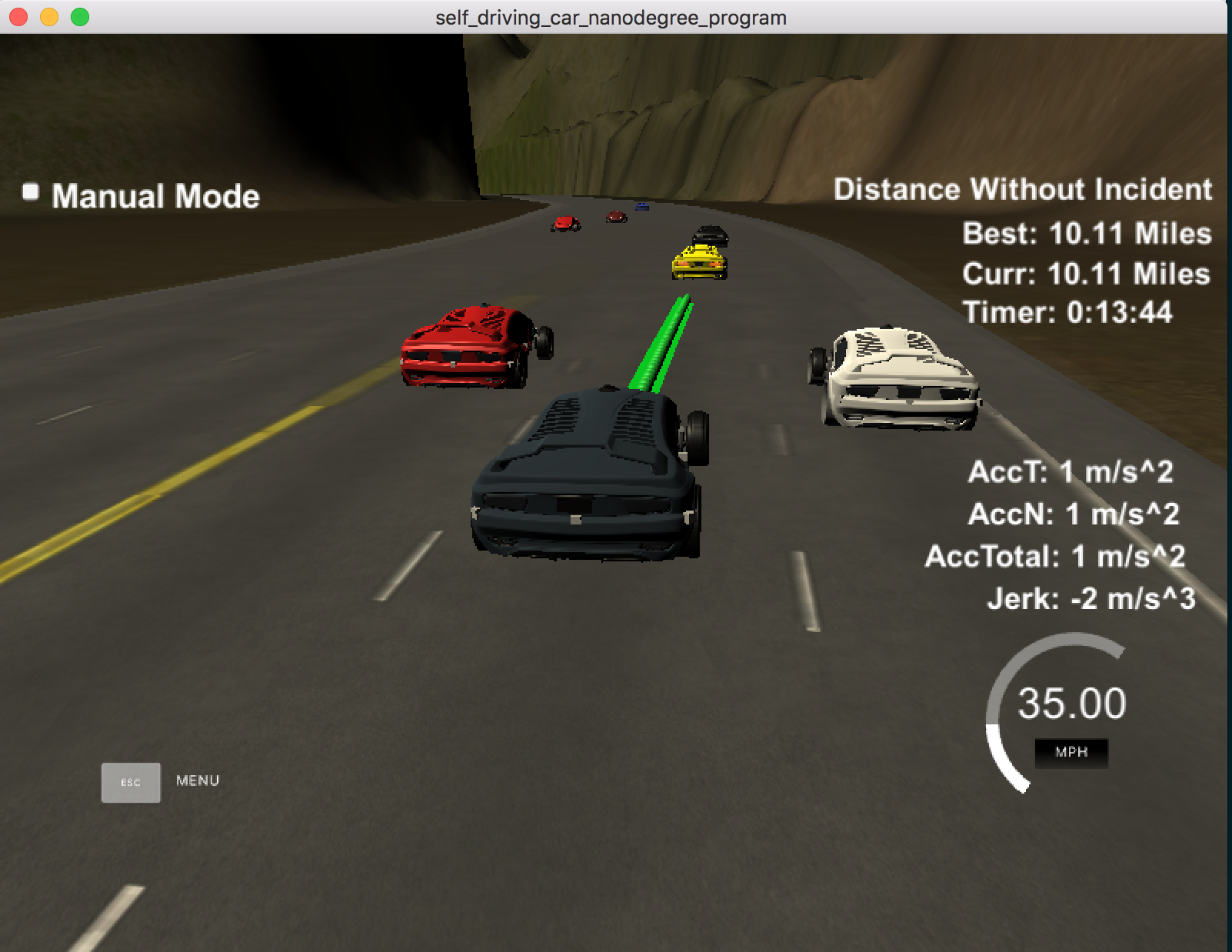

The ego car can safely drive around the entire track at just under 50 miles/hour, without any violations. I ran the simulator for various lengths (5 miles to 12 miles) successfully.

Here is a resulting video showing a successful 5-mile drive.

Improvements

The ego car drives itself fully autonomously along the entire highway track. However, there are limitations because of the simplified logic. Since the ego car prefers to stay in its lane and test for a safe left lane first, it can get stuck behind a slow moving car if there’s traffic in the left lane, even if the right lane is empty, although it does find its way correctly. Also, at times, the ego car can switch back and forth between Left lane to Center lane, due to traffic ahead, although this too is eventually handled.

Secondly, currently only implicit costs are awarded for lane change behavior. That is, the costs are binary 0/1 if a lane is safe to move into or not. A better alternative would be using true cost functions that give varying costs based on:

- trajectories available

- traffic in neighboring lanes

- acceleration / jerk values

- collision avoidance

Thirdly, a Jerk Minimization technique could be used that smoothes out, using a quintic polynomial, the possible trajectories available to the ego car.

Fourth, one could project the future behavior of traffic and try to predict their trajectory and thus make the car more proactive.

Code

Code for this project is on my repo

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to David Silver and Aaron Brown at Udacity for clearing up many of the concepts. 🙏🏻