If you live in the Silicon Valley (as I do), you cannot help but hear almost everyday of a self-driving car startup claim that it has crossed so-and-so million miles of training on public roads. In my neighborhood alone in Mountain View, everyday I count a few dozens Waymo’s robotic Pacifica vans, Drive.ai’s car, and others, navigating the crowded Castro street, while pedestrians and other vehicles nonchalantly steer their way in and out of their paths. Compared to two-three years ago when many pedestrians (and several car drivers) would stop midway to gawk at these vehicles, today they seem unconditioned, as if accepting the reality of autonomous vehicles in our midst. Have these citizens accepted the inevitable robotic dominance? Have we reached the point where autonomous vehicles (AVs) can start replacing weary humans driving up and down Route 101?

That future is a long way off. But what does is mean to claim that AVs drive more safely than humans? I have been fascinated with this query since I first saw one of these cars navigate swiftly on the street, and subsequently had a chance to make one prototype run autonomously.

But first, how does human driving fare? In a word, humans are safe drivers in aggregate, but not safe enough.

The human driving traffic safety record

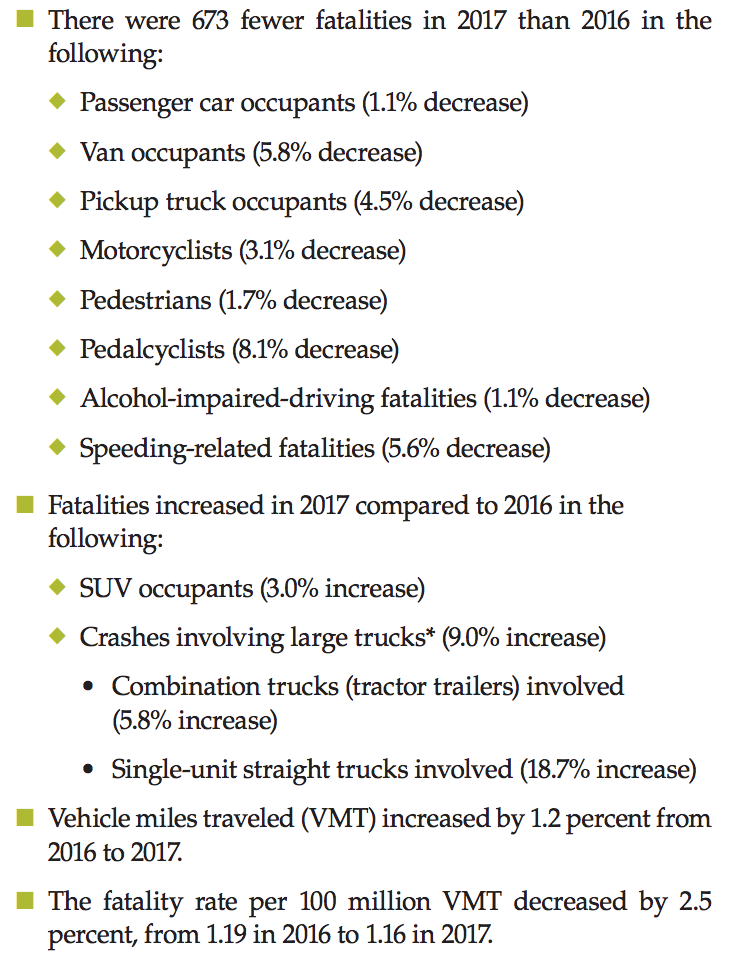

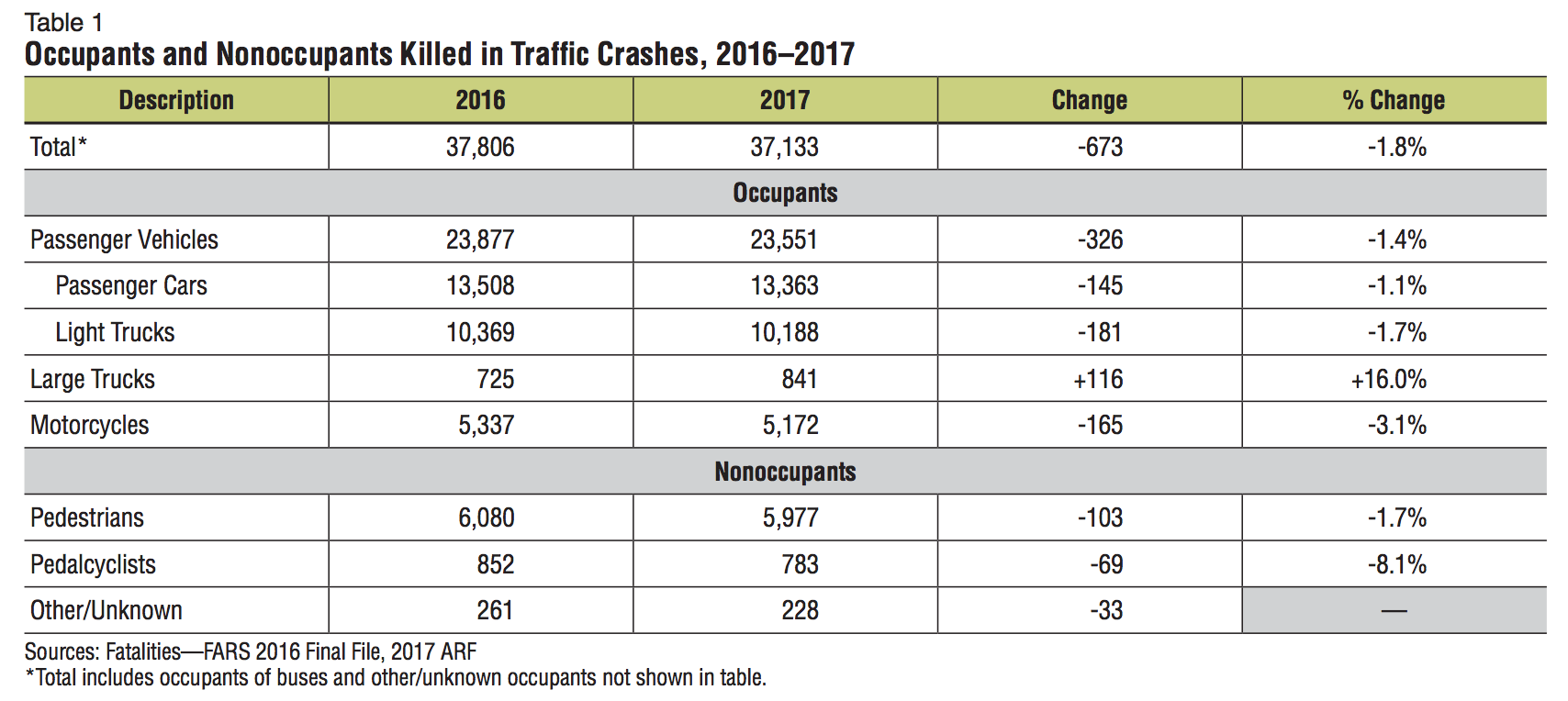

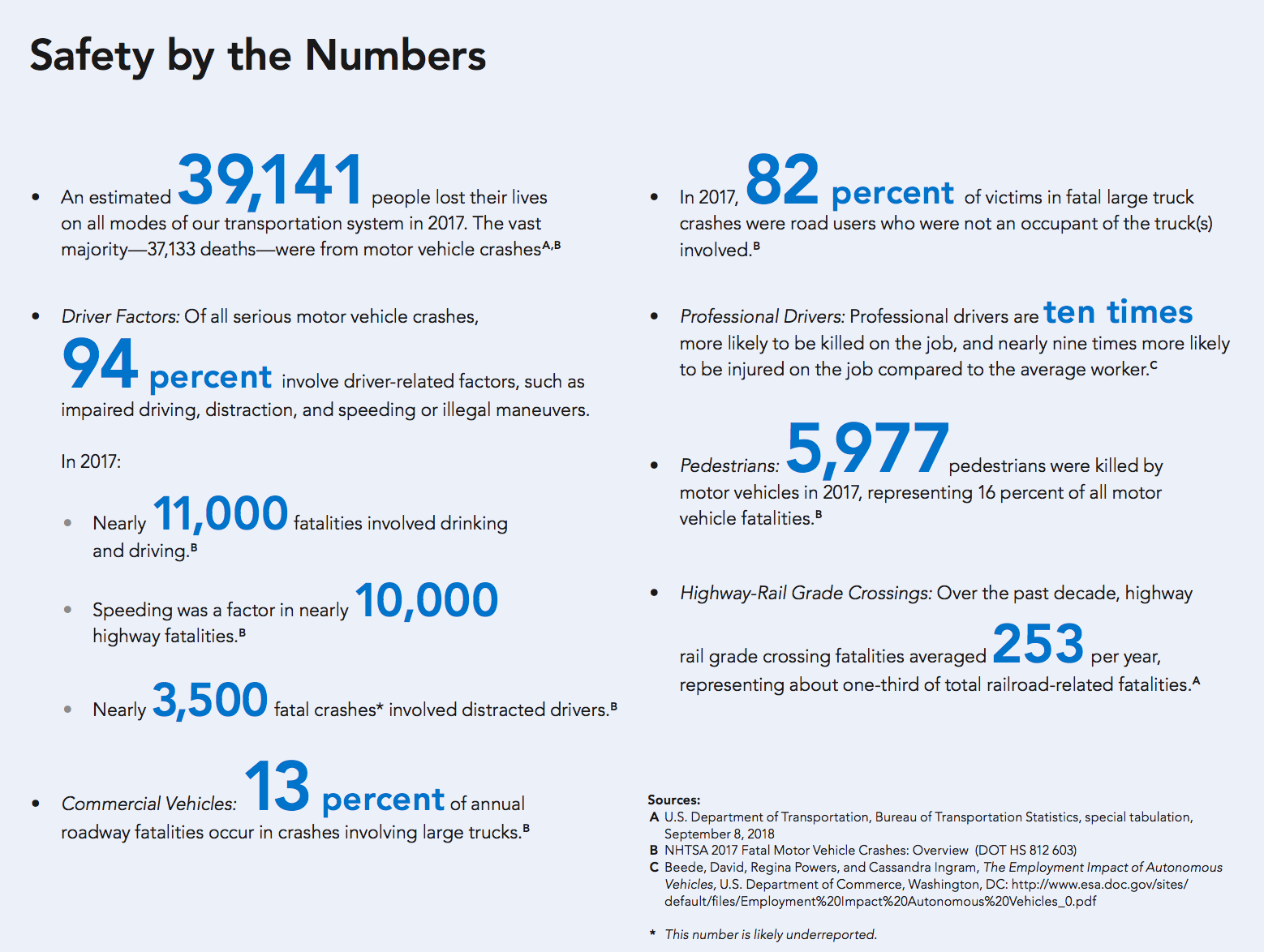

The recently released stats from NHTSA, one of the agencies that governs rules and regulations for motor vehicles in the U.S., claims that driving got just a bit safer in 2017, with about 37,133 reported traffic fatalities, a 1.8% decrease compared to 37,806 in 2016. [Source: NHTSA - 2017 Fatal Motor Vehicle Crashes] This fares better than the previous two-year trend when traffic fatalities had increased in 2015 and 2016. That’s the good news. The bad news? It’s still over 100 traffic-related deaths per day in the US. And SUV related crashes are still worse.

Overall, vehicle miles travelled in the US increased by 1.2% from 3,174 billion miles (2016) to 3,213 billion miles (2017). That’s over 3 trillion miles driven in about 260 million registered vehicles by over 216 million registered drivers. That’s a whole lotta vehicles and a whole lotta drivers. The mind boggles.

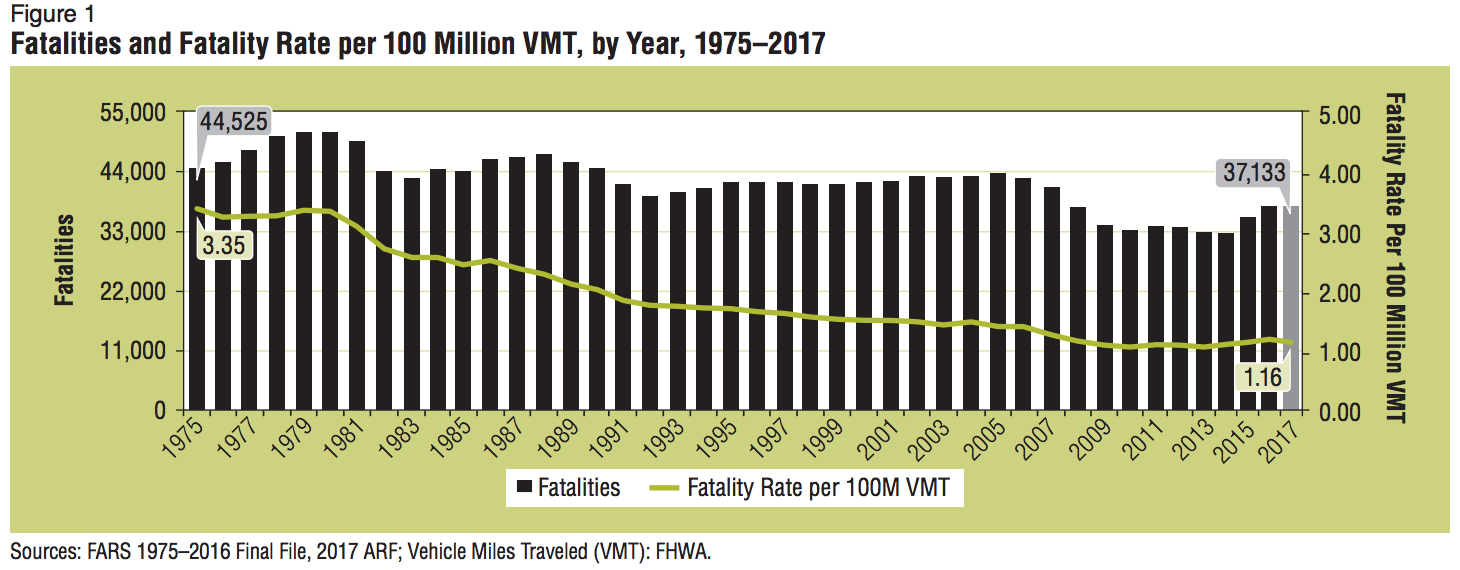

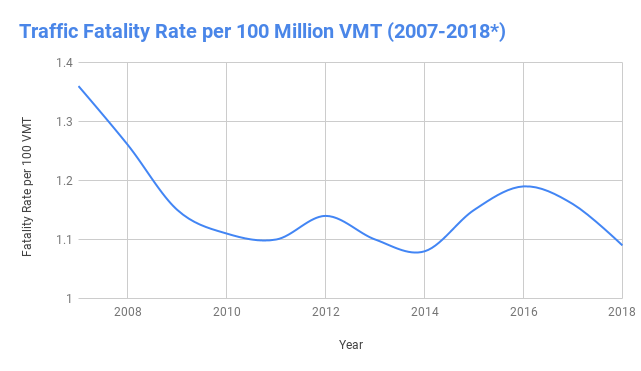

The stats nerds and policy geeks count safety numbers as Fatalities per 100 million vehicle miles traveled (VMT). That stat, which was a high 3.35 in 1975, is down to 1.16 in 2017 and further 1.09 (estimated) in 2018. Does that mean drivers have gotten better? Or have we suddenly started following rules? Or has technology helped us? It’s a combination of all, and more.

That means, we humans cause just over 1 traffic death in over 100 million miles of vehicular travel in the U.S. On an average basis, that is an astoundingly low number. Yet, on an aggregate basis, 37,000 deaths is a several thousand deaths too many. In an ideal world, all of us would drive safely and there would be no deaths. How close are we to that scenario?

Over the last decade, the fatality rate has been in the 1.09-1.36 per 100 million VMT range, which is to say, reasonably safe, but it could be better.

What are the kinds of fatalities?

Fatality Composition

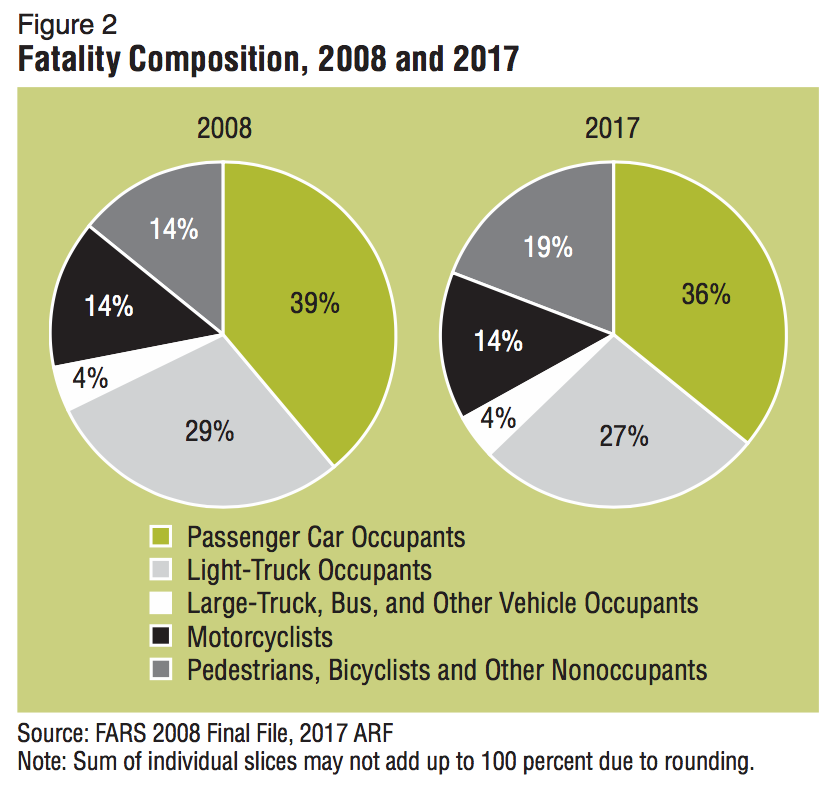

Who are the people affected in these accidents? The NHTSA has some stats on that as well.

In the last few years, urban accidents have risen more than rural accidents.

So, not only are thousands of occupants killed in traffic accidents, but also over 6000 non-occupants are killed. These include pedestrians, cyclists, motor-cyclists, and others. So traffic accidents have huge externalities in terms of costs of medical care, property damage, lost productivity, lost wages, and more. Some estimates of care and damage run about $850 billion per year on an aggregate basis (McKinsey? NHTSA?). As if the loss of one life wasn’t enough, this is a huge economic loss on top of that.

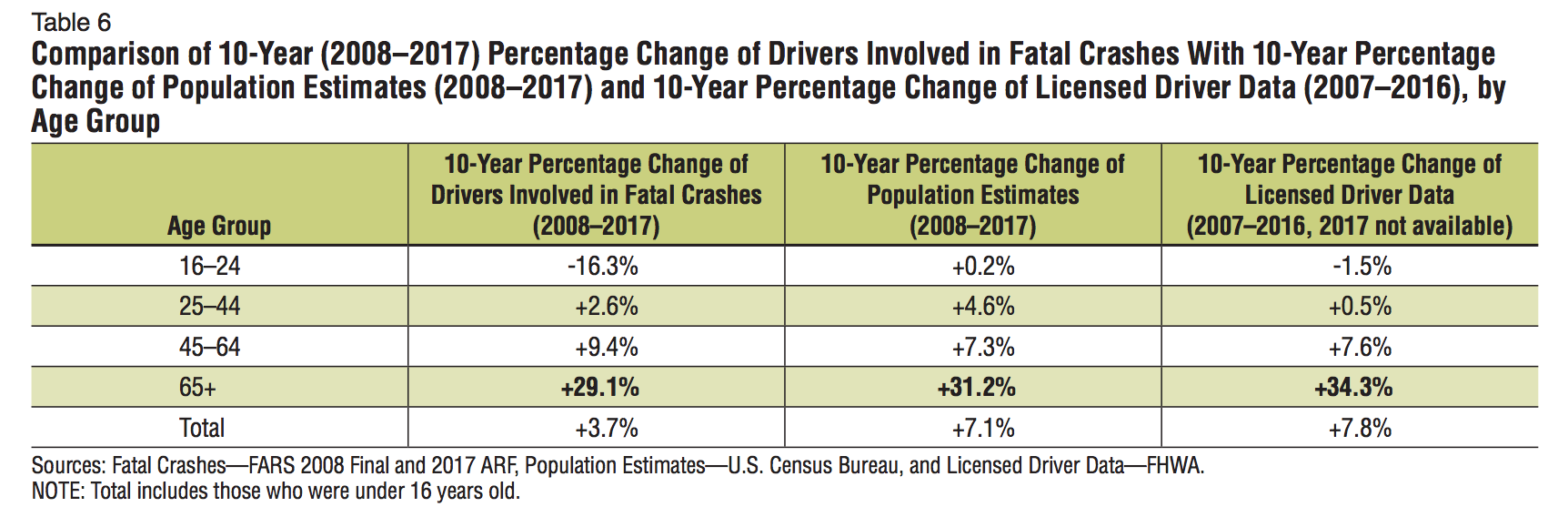

Who are the people who die in accidents? NHTSA data again shows that older drivers (65+) are now much more likely to be involved in accidents than younger (25 or below). This is interesting to note, given the demographically speaking, the population is aging in the US (as it is elsewhere). So, net-net, drivers are getting older, and despite all the tech advances, there are over thousands of accidents, caused largely by humans.

Causes of Accidents

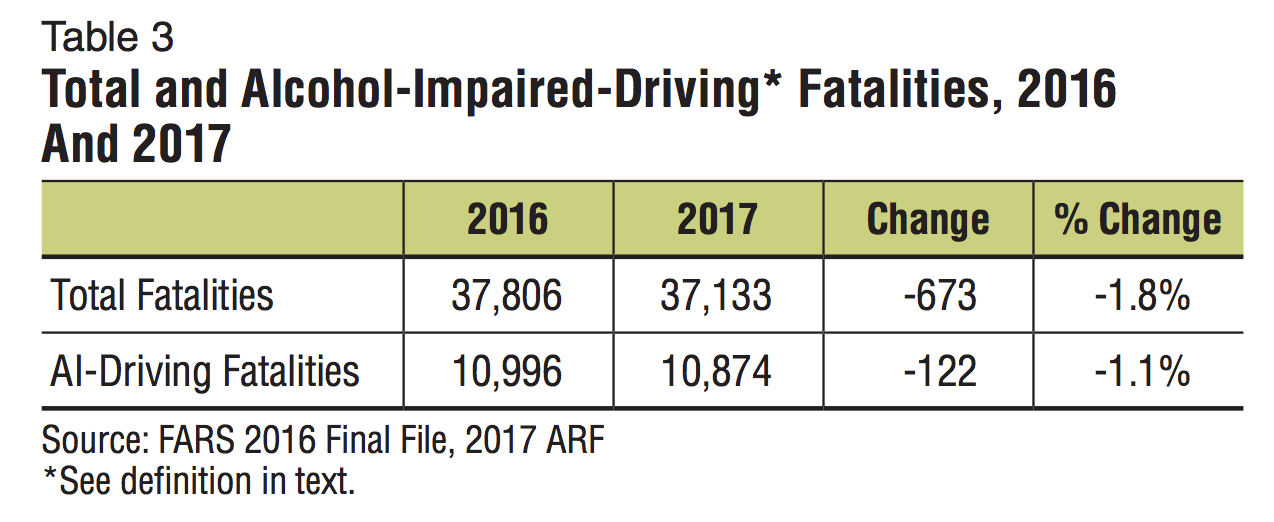

So, what causes these traffic accidents? NHTSA estimates are around 94% of accidents are caused by human errors. These involve impaired driving (e.g. drunk driving, sleepy drivers), illegal maneuvers (speeding, not following the road rules), distracted driving and more. Over 29% of deaths are due to drunk driving. That’s almost 11,000 drunk-driving deaths. Speeding alone causes over 10,000 deaths per year. [For more stats, see here Road Safety Facts — Association for Safe International Road Travel]

What If

What if — hear me out on this one — what if drivers actually followed the rules of the road?? Would we get any safer? If you’ve driven on Route 101, or take your favorite highway to hate on, you too be wondering this question constantly when you are slowly trudging along in the middle of traffic jams and you see some random dude (it’s always a dude, bro) swerve his Tesla in an attempt to get out of it. Nice try buddy, but you just gave a dozen people a scare of their lives.

And while humans are, on average, safe enough drivers, in specific instances they can be awful. They are tired, they are always in a hurry, they are irritated, they are distracted, drunk or sleepy, and sometimes all at the same time. And they cause accidents. While the fatality rate could reach lower, I believe (as do many experts) that there’s a floor, a lower limit to this fatality rate; perhaps it is 0.8 fatality per 100 million VMT, perhaps it is lower. But this lower limit exists because it is humans who drive, with all their faults.

So much for the bad news.

Can technology help? And to what extent? And in which cases? That’s the promise of autonomous vehicles, which I’ll cover in the next post. Stay tuned.